2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Press release of June 1207 Announcing Arrival of the Proto-Renaissance

This imaginary and preposterous press release from the Florence Shopping News, of June 1207, demonstrates how we architects like to imagine the creation of great architecture; and this is how I had hoped to find the documentation of the design and construction of an important monastery church, such as San Miniato al Monte. Instead, what I uncovered was a process of site development that required a thousand years, in order to achieve the completed structure of the current church. Then this process generated another millennium of related development that arguably still continues. In the process of investigation, I discovered a series of fascinating, anecdotal historical topics, each one a potential research topic in its own right, that I have placed in various side-bar locations.

The year 1207 was indeed an important year in the history of San Miniato al Monte, as it was the first opportunity to see the entire church completed. But, I feel that the true importance of the year 1207 is more symbolic, as the site was finally assured a permanent place in the landscape of Florentine icons.

This article addresses three issues regarding the development of San Miniato:

1) What is the early history of San Miniato al Monte and why did it develop in this particular location?

2) What were the primary phases of its construction and how were those phases determined by architectural historians?

3) Why is the year 1207 significant in the history of San Miniato, and what subsequent development was generated as a response?

Considered together, these points will demonstrate that the “genius” associated with the creation of San Miniato is not attributable to the effort of any one individual, but the result of a collective contribution of many players over a very long period of time. All the same, the result is a work of architecture that possesses natural balance and a perceived unity that was capable of inspiring the future architectural aesthetic of Florence and its urban development.

Part 1a—What is San Miniato al Monte?

San Miniato al Monte is the ever-visible, “white” Romanesque church “up in the hills.” It seems to hover over the Medieval city of Florence as though to contrast deliberately with its more monumental competitors—the Duomo, the Giotto Campanile and the tower of the Palazzo Vecchio. Common knowledge indicates that it is named for a certain Saint Minias (San Miniato) and that he probably was an early Christian martyr.

But the site that is occupied by the complex of buildings that comprise San Miniato al Monte has significance that extends back to the first settling of Florence by the Romans in 59 BC. At that time the hill was called “Elisboth” or “Elisbots” signifying “woodland sacred to divinities” and perhaps “the sun” because of its eastern relationship to the Roman colonia. As the colonia developed into a municipium, so too the name of the hill changed to “Mons Florentinus,” but retained its identification as a place of pagan worship.1

A number of myths exist about the events surrounding Saint Minias, but the most pervasive has Minias as a Syrian or Armenian prince who had come to this part of Italy to promote the new religion of Christianity. Although Roman Florence had managed to stay out of the pagan/Christian debate up to now,2 Minias would become its first exception and its first martyr. In the year 250 Emperor Decius had ordered the persecution of Minias to set an example. Minias was ordered into the amphitheater to satisfy the appetites of various voracious animals, but, so goes the story, he managed to subdue them with his gentle demeanor and prayer. He survived a number of similarly daunting trials, but, unfortunately, not the final one—for out of frustration, Decius ordered Minias to be beheaded on 25 October 250. As the best myths have it, he picked up his head and managed to walk—or better yet, fly, accompanied by angels—to the top of Mons Florentinus and selected his own final resting place, thereby becoming the first Christian martyr in the history of Florence.3

Notizie Mercantili Fiorentino

Issue VI Volume MCCVII

New facade Revealed

Proto-Renaissance Arrives in Florence

Middle Ages Declared Officially Over

It was a beautiful June day. The entire city of Florence has been abuzz with excitement – the new facade of San Miniato al Monte, after nearly three years of secretive work, was just revealed to the public. In a public spectacle and a spirit of partnership typical of the times, the Signoria of the city and the Benedictine monks of San Miniato, collaborated on a magnificent public event. Townspeople had been making their way across the Arno and up the “monte” for the mid-day event. Precisely at noon, after the obligatory pomp and speeches, a cord was pulled and the covering over the facade dropped softly to the ground. The crowd gasped with a combination of awe and disbelief as they caught their first glimpse of the shimmering, white facade of San Miniato al Monte. Suddenly everyone knew that the “proto-Renaissance” had arrived. Whispers spread through the crowd: who is the architect…who is this genius?

Advertisement

Special this week, only

Crossbows, catapults and battering rams

XX% off Only at Mercatowal

However his body may have arrived there, the loyal followers of Minias managed to maintain a tomb, which, also was used for clandestine early-Christian meetings. With the acceptance of Christianity in the fourth century, the first conspicuous built structure—a small “chiesuola”—was placed over the tomb of Minias.

The site was magnified in importance as the result of a visit by Charlemagne in 781. On his way back to Gaul, from Rome, he spent time in Florence with his new bride, Hildegard (Ildegardo). Originally from Tuscany, she had been aware of the Minias site and walked Charles up to the sacred place in the hills. After her premature death, only two years later, he was so moved by this recollection, that he sent a donation to build a proper church on the site, and in her memory –

“...et pro anima bone memorie dilectissime coniugi mee Ildegarde quondam ad Basilicam prefati martiris Christi Miniatis sitam Florentie ubi ei venerabile corpus requiescit...”4

"...and for the soul of my beloved spouse Hildegard of good memory, once at the Basilica of the aforesaid Saint Miniatus martyr located in Florence where his venerable body rests..." [Translation, courtesy of Paolo Bonavoglia.]

In spite of this investment Saint Minias's fate and fame were not yet secure. Due to a combination of difficult times that Florence was going through, and a general lack of interest in Christianity, the little church fell into ruin, and worse, the body of Minias was stolen by saint-deprived Germans.5

The existence of the current church and the permanence of the San Miniato myth owe their existence to Bishop Hildebrand (Vescovo Ildebrando), who observed the state of building ruin and the missing saint and vowed to correct both conditions. In 1018 he arranged for donations and ordered the setting of foundations for a new, larger church that could be constructed around and over the existing structure. To solve the other problem, the missing saint, he assigned one Drogon to be the first abbot of the monastery, but with the stipulation that he write a “history” of Saint Minias, the martyr, which would include the rather convenient rediscovery of the bones somewhere on the hillside.

“In consequence of this unfortunate abduction, Bishop Hildebrand faced a serious difficulty as soon as he approached the execution of his grandiose design. A monastery dedicated to the Florentine saint must imperatively possess his sacred remains. For a less resourceful man than Hildebrand the problem might have proved unsolvable…(but when) the cunning bishop ordered a search for Miniato’s bones to be conducted over the hillside, his pick and shovel squad found them without any difficulty.”6

Construction began in the style of masonry construction and marble decoration that was prevalent during the 11th century in Tuscany—a style now referred to as Tuscan Romanesque—and identified by a continued interest in a “sense for Classical order and geometry.” The inspiration purportedly was imitative of Roman ruins, but as a style it can not be considered historically accurate, in the same manner as we would find later, during the Renaissance. Contemporaneously, it was being utilized and developed in a number of other ongoing Tuscan building sites, notably the Baptistry of San Giovanni, the Badia of Florence, and the churches of Santa Reparata, San Pier Scheraggio, and Santi Apostoli.

Giusti elaborates:

“San Miniato and the Baptistery are both typical examples of Florentine Romanesque architecture, which selects architectural elements drawn from Classical and Early Christian antiquity, Byzantine art and the Po Valley and Pisan Romanesque styles, and blends them into a new and deeply original language.”7

Hildebrand—saint or sinner?

Schevill, pp. 41 48

“The bishopric became the prize of ambitious, worldly men who spent their days in riotous living and squandered the possessions entrusted to their care among favorites and harlots.”

“And so we come to Bishop Hildebrand, who was a most worthy successor of his immediate predecessors in that he bribed his way to office, did homage to his lord, the emperor, as though the bishopric were nothing other than an imperial fief.”

“Possibly the stout old sinner on the cathedral chair began himself to be troubled, if not by mounting moral compunctions, at least by the increasing hostility of his subjects. Be that as it may, the time came when he resolved to found a monastery. It comports best with his character to refer his resolution to his active self-esteem and love of splendor, but, like other Medieval men, he also hoped to have the reckoning of his sins reduced or even canceled out entirely by so signal a service to the Christian faith as the founding of a monastery was universally held to be. His first step was to choose as the site for his establishment the low hill overlooking Florence from across the Arno to the east and designated by tradition as the burial place…of San Miniato.“

Why was Charlemagne’s church neglected?

Schevill, pp. 8-9, 43

“Contrary to the flattering legend which gained currency among the Florentines in the Middle Ages, the new faith did not establish itself solidly on the banks of the Arno till at a relatively late period and long after the days of the apostles. Moreover, the first authentic Christians who appear as residents of the provincial Roman city were not even native Florentines but itinerant traders from the eastern Mediterranean.”

“That the probably feeble Greek colony in pagan Florence for a long time had very little success in making converts is indicated by the fact that in the persecution of the Emperor Decius in 250 A. D. the single Arno inhabitant to suffer martyrdom was Minias – a Greek.”

“The Minias worship, however, never became popular, for, when some five or six centuries later we get news of the chapel, we learn that it had been permitted to fall into decay and the instituted service to be neglected. Let the fact remind us that the Italians by no means uniformly cherished the memory of the early heroes of the faith.”

“…neglect and indifference went the extraordinary length of permitting, apparently without a protest, a relic-hunting German bishop…to exhume the bones of Miniato and carry them off in triumph to distant Metz in Lotharingia.”

Part 1b—What Was Significant About this Location?

I have already mentioned that Minias chose to deposit himself on sacred grounds, or more likely, his followers had carried his body to Mons Florentinus, because the site was long regarded as being sacred. But why would Hildebrand choose this particular site to re-develop when it was outside the fabric of the rapidly-developing urban Florence? Were his motives based on piety and the sacredness of the site, or was there something else about this particular location that secured its destiny? Admittedly, it may simply have been his desire to stay out of the ever-cantankerous city; but this location was imbued with great strategic importance, if one wanted to establish a monastery, by bridging the agrarian lands with city life and presenting itself to the roads out of Florence to points south.

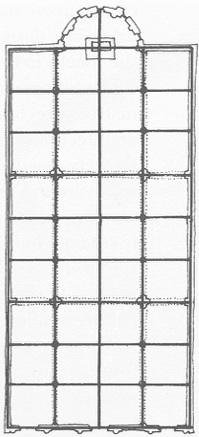

Trachtenberg observes that “…early Florentine buildings such as San Miniato al Monte…are each symmetrically organized around a single horizontal or vertical axis…” and refers to “...the axio-centric thinking of Florentine planners…”8

To the casual observer San Miniato may “hover over Florence” like a billboard announcing sanctity and religious experience; but the orientation of San Miniato does not appear to relate to the city of Florence, per se. It relates instead to the Oltrarno side of the Ponte Vecchio, or to be chronologically correct, the point where the Roman bridge crossed the Arno. In contrast to in-town projects such as Santo Spirito, San Miniato was built on a relatively flexible site and could have been adjusted to face the city if that had been so desired, but it clearly faces the point of landing on the south side of the Arno.

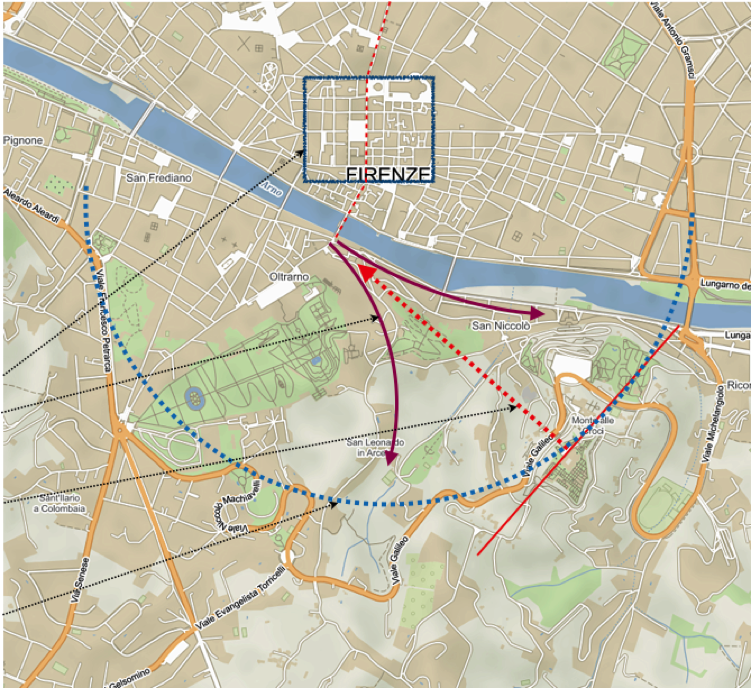

[As an experiment, using a map of Florence, the axis of San Miniato was extended across the landscape to verify this assertion. See map below.]

Pratesi observes that at the time of development under Hildebrand, Florence had become a “stazione” for pilgrims from the north on their way to Rome.9 Once having crossed the Arno, they would have used one of two available, yet divergent, Roman roads with San Miniato happily positioned between the two,10 as though to suggest “last chance for sanctity and religious experience for the next 100 miles!”

Part 2—Phases of Construction

One of the confusions and controversies about the construction about San Miniato al Monte is the question of when exactly it was constructed. Tourist guidebooks and history books that do not rely on historical accuracy, may give the date “1018,” which is recognized as the date when construction began; yet inscribed into the zodiac marble flooring is the year “1207,” which implies completion of the interior. Between the laying of the foundations in 1018, under Hildebrand, and the completion of the facade in 1207, there is no written documentation that would help date the construction of San Miniato.

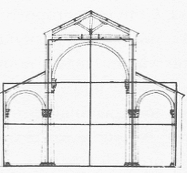

All the same, Walter Horn has demonstrated that “San Miniato is not a uniform and homogeneous structure…”11 as was once believed, but was constructed over three or four discernible phases of construction after the setting of the foundations. Inspired by earlier studies of Ulrich Middeldorf and Walter Paatz, he developed a two-step process to identify these periods: first, he inspected the entire structure and located those places where there are changes in use of materials or methods of workmanship, and applying reasonable logic that the work proceeded from the bottom up and from east to west, was able to isolate the phases of work.

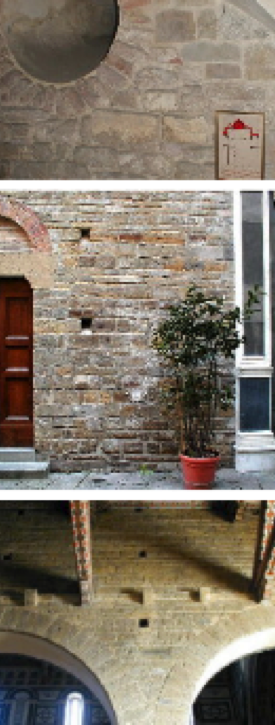

He then compared the masonry work of those identifiable phases to contemporary building projects, notably the Baptistry of San Giovanni, the Badia of Florence, and the churches of Santa Reparata, San Pier Scheraggio, and Santi Apostoli, which offer clearer dates of their commencement and/or completion. (See photos at left for typical examples of his methodology.)

From these assumptions he was able to conclude the following progression of work:

1018

1062

1070-1093

1128-1150

1175-12072

It is worth re-emphasizing that the marble facade was not applied after the front elevation was completed, but was applied as the wall rose to each respective order.13 A similar effect can be seen in Siena where the intended expansion of the Duomo already has marble applied even where work was still under way. Therefore the front elevation can be better understood as two distinct designs created about 100 years apart.

The lower half clearly is more “Roman” in its sources and uses decoration in a simple, geometric manner that reinforces the intent of the colonnade. The upper half is free in its use of decorative elements and diminishes references to the Roman style.14 The mosaics are of a period later in the 13th century; and it is possible that the false doors on the lower level and the “oculi” windows on the upper level were added at a later date, as well.15

Minius during happier days.

Use of proportion at San Miniato

Trachtenberg, pages 159 –160

“In Florence the Medieval use of geometric figures and consonant ratios has often been noted, but their penetration of architectural design has been overshadowed (when not suppressed) by the scholarly obsession with unravelling the proportional schemes of Brunelleschi and his followers, a pursuit colored by the misbegotten idea that quattrocento architecture had proportions whereas somehow the trecento didn’t.”

“In reality not only did Medieval Florentine architects shape and proportion their design comprehensively in a rigorously contemporary manner, but their proportions are exceptionally lucid…”

“This lucidity appears in stark Romanesque clarity not only in the Baptistery, with its 1:1 proportions of diameter and height…but also in the layout of the other major monument of the period, S. Miniato al Monte, which is based on the classic early Medieval system of ‘square schematism’… (where) …a square module underlies the entire plan…and is also a determinant of the cross section.”

Urban Fabric during the 11th Century

Fei, Sica, et. al. Firenze: Profilo di Storia Urbana, p. 28

“This tangle of streets had few open spaces and no piazzas (except for the church courtyards and the forum vetus, where the market is now located, at the center of the grid). The new monuments, the church of Santi Apostoli within the walls and the church of San Miniato in the hills to the south of the Arno…along with the baptistry…stand out in the residential fabric for the stylistic discipline of their construction, based on the simplification of geometric forms and derived from Roman and Christian structures, already laying down the groundwork for humanism’s renewal of the architectural culture.”

Top to bottom:

Siena, uncompleted Duomo with marble facing in place.

San Miniato al Monte original order of ca. 1093, based on a Roman colonnade.

Upper order of facade finished ca. 1207, suggestive of a temple.

Note that the mosaics were added later, during the 13th century, and are not really consistent with the original intent.

Top to bottom:

Santa Reparata—pre-Romanesque—rubble, free-form

Santi Apostoli—ca. 1075—horizontal layering

San Miniato—middle phase, ca. 1100—smooth, even stonework, deliberate archway and window openings

Foundations laid by Hildebrand (already established by earlier historians)

The crypt was constructed and the layout of the floor plan had been determined.

Side naves were constructed as well as the lower “order” of the facade, including its marble facing.

Demolition of the existing, encapsulated church, thereby opening the interconnecting bays.

Erecting upper order of facade, including upper, marble facing, completion of interior finishes such as floor paving and interior architectural elements.12

Unidentified scene from the early 19th century.

Firenze e le Sue Colline by Luciano Artusi and Vincenzo Giannetti. No reference to artist or title.

Location of the Roman "colonia" of 59 BC and the north-south road cutting through the Roman town.

Roman roads still in use during the Medieval period.

Axial alignment of San Miniato towards the Oltrarno side of the Ponte Vecchio and the pre-existing, Roman bridge, taken as a perpendicular to the face of San Miniato.

Hypothetical continuation of the 13th century comunal walls based on topographic maps at the museum Firenze Com’Era, suggesting that the fortress that San Miniato is set on would have been part of the city fortifications.

It appears that difficult hillside terrain, and the recurring plagues, were obstacles to further wall construction and a need for more land development.

Partial map of Florence showing orientation of San Miniato al Monte in relation to the Oltrarno side of the original Roman bridge and/or the current Ponte Vecchio.

1) The first version of the Ponte Vecchio dates to 966, and either assimilated, or was built adjacent to the Roman bridge. Either way, this was the only crossing until 1218.

2) The current church, the foundations of which were laid out in 1018 by Hildebrand, was built around the previous small structure, unlike Santa Reparata, which determined the geometry of the Duomo. The final orientation of the foundations would have been determined at that time.

San Miniato al Monte

Roman bridge