10

11

12

13

14

9

Part 3a—The Significance of the Year 1207

The completion of the monastery church in 1207 signified two important turning points in the existence of San Miniato al Monte—one is tangible, the other symbolic. The tangible, first point concerns the physical, constructed fabric. By the year 1207 there is at last a permanent, single structure that both figuratively and literally is built on the layers of meaning that the site acquired over the previous millennium. One could interpret that the building was built as a response to its site history. The reason I consider this a turning point is that after 1207 most development of the site resulted in related, but physically separated construction: the bishop’s palace (1294—1320); the campanile (1523); military fortifications (during the 16th century); the grand staircase breaching the fortress walls; and during the 19th century, when the fortifications were no longer perceived as necessary, their conversion into a grand necropolis. [See the aerial photo on page 12.]

It had become established as a monastery that, except for periods of political interference, has survived until the present. Thanks to the initiative of Hildebrand, whatever his motives, its structure was built competently, so that it did not again fall into ruin, as with the original building donated by Charlemagne.

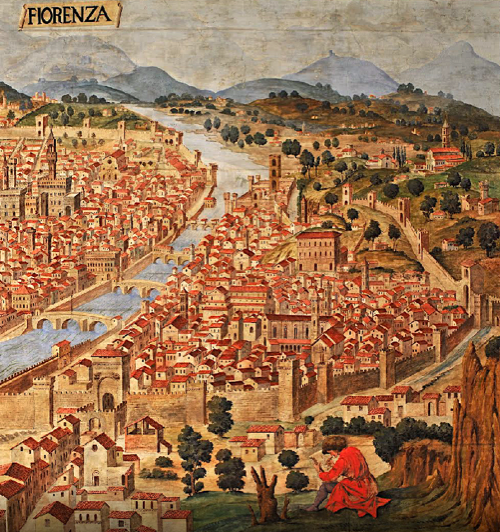

The perception of permanence leads to the symbolic meaning of the year 1207. The true significance of the year 1207 is that San Miniato had become a permanent fixture in the Florence landscape and influential in the subsequent development of Florence and what was to become its particular design aesthetic.16 There may be no intelligible views of Florence from the 13th century, but there exist many views and maps of Florence from the 15th century on. Most all of these clearly include San Miniato in the background as part of the developed landscape.

Part 3b—What Subsequent Development Was Generated in Response?

Both Brunelleschi and Alberti are acknowledged as having developed styles of architecture that attempt to be responsive to a local aesthetic. For their Florence projects each developed a style that combined the aesthetic of Roman-inspired religious architecture juxtaposed with an opposing, and imposing, aesthetic of the fortified palazzo. Brunelleschi and Alberti:

…non furono nemmeno consapevoli di quanto era veramente nuovo nel Romanico Fiorentino; forse, cioé, pensarono di attingervi per quanto in esso riviveva l’Arte Classica romana, di cui erano ferventissimi ammiratori. Paradossalmente si puó dire che gli artisti rinascimentali, quasi senza rendersene conto, trovarono a casa propria, a Firenze, nel Romanico Fiorentino, particolarmente nella Basilica di San Miniato e nel Battistero di San Giovanni, quelli ideali artistici della romanitá classica.”17

Regarding Brunelleschi, Tavernor states:

“It is reported that Brunelleschi and Donatello had surveyed Roman monuments…. Roman remains were certainly closely studied by successive generations intent on a similar path. However, while Brunelleschi and Donatello were pioneers…there are doubts whether the physical remains of Rome were their primary source: the Florentine Baptistery was in any case thought to be Roman, and its appearance, along with the churches of the Santissimi Apostili and San Miniato al Monte, bear more obvious comparison with Brunelleschi’s designs.”18

Similarly, Pratesi observes that Alberti’s house in Florence was along the Arno facing San Miniato. Every morning, weather permitting, Alberti would climb up the hill to visit San Miniato to admire its elevational design.

“L’Alberti, con cui si puó fare iniziare l’Architettura Rinascimentale fiorentina, sicuramente é stato un fervidissimo ammiratore della Basilica di San Miniato. Dalle finestre di casa sua nell’attuale via dei Benci, sulla riva dell’Arno, vedeva di fronte la facciata della Basilica. …l’Alberti, tutte le mattine, se non glielo impediva la pioggia, attraversando l’Arno per il ponte alle Grazie, faceva il suo footing salendo il Monte di San Miniato, per andare ad ammirare la Basilica. … La testimonianza di questi rapporti ideali tra l’Alberti e il Romanico di San Miniato si ritrove evidentissima nella facciata della chiesa di Santa Maria Novella…”19

...that Alberti built at Santa Maria Novella for the Rucellai family. A *casual observer might conclude that both facades were by the same designer.

“In its arrangement of architectural elements (a pedimented temple-like upper storey with triangular panels and scrolls placed on a broad base) and the rich geometrically patterned marble inlay surface in white and green marble…, Alberti’s design resembles the general ornamental qualities of the Florentine Baptistery of San Giovanni, and especially the twelfth-century facade of San Miniato which overlooks Florence.”20

[*We are not "casual observers." In the next article: From San Miniato al Monte to Sant'Andrea

The Clarification of a Renaissance Ideal, we will look at the remarkable differences.]

Conclusion

I have traced the development of the basilica church of San Miniato al Monte as a Romanesque, “proto-Renaissance,” Florentine icon and demonstrated that it was not the result of a single event or a single creative moment of design, but represents a long process of development spanning over a thousand years. As the built fabric developed over time it was responsive to its setting and points of approach. Once it was extant as a “complete” structure, a condition it finally achieved in 1207, it was to generate additional site development that extended well into the 19th century. Finally, even though San Miniato al Monte is the result of centuries of human effort and intervention, its seemingly-unified style inspired two influential architects of the Renaissance—Alberti and Brunelleschi—in their own projects for Florence, and thereby it had become a catalyst for the architectural style that was to become the Renaissance.

Notes:

1. Licia Bertani, San Miniato al Monte, Becocci Editore, Firenze 1999; page 9.

2. Ferdinand Schevill, Medieval and Renaissance Florence – Volume I: Medieval Florence, Harper and Row, New York 1963; pages 8 – 9.

3. Piero Bargellini, Florence the Magnificent: A History, Vallecchi, Firenze 1980.

4. Alberto Busignani, Raffaello Bencini, Le Chiese di Firenze – Quartiere di Santo Spirito, Sansoni Editore, Firenze 1974; Document 87: Donazione di Carlo Magno, page 217.

5. Schevill, page 43.

6. Schevill, page 44.

7. Annamaria Giusti, the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence, Mandragora, Firenze 2000; page 17.

8. Marvin Trachtenberg, Dominion of the Eye, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1997; pages 159 -160.

9. Franco Pratesi, La Splendida Basilica di San Miniato a Firenze, Octavo, Firenze 1995; page 79.

10. Pratesi; pages 67 – 68.

11. Walter Horn, “Romanesque Churches in Florence,” the Art Bulletin, XXV 1945; page 112.

12. Horn; page 114.

13. Horn; page 115.

14. Horn; pages 114 - 115.

15. Pratesi; page unknown.

16. Giusti; pages 17, 52. Even though San Miniato and the Baptistry represent concurrent periods of construction and San Miniato followed the design of the Baptistry, the Baptistry copied the intartia zodiac floor designs from San Miniato after putting up with brick paving for decades.

17. Pratesi, page 297.

18. Robert Tavernor, On Alberti and the Art of Building, Yale University Press, New Haven 1998; page 5.

19. Pratesi, page 296.

20. Tavernor, page 99.

Bibliography:

Piero Bargellini, Florence the Magnificent: A History, Vallecchi, Firenze 1980.

Licia Bertani, San Miniato al Monte, Becocci Editore, Firenze 1999.

Gene Brucker, Florence: The Golden Age, 1138 –1737, University of California Press, Berkeley 1998.

Alberto Busignani, Raffaello Bencini, Le Chiese di Firenze – Quartiere di Santo Spirito, Sansoni Editore, Firenze 1974.

Cesare De Seta, direttore, Le Citta Nella Storia d’Italia, Editori Laterza, Roma-Bari 1997.

Silvano Fei, Grazia Sica, et. al. Firenze: Profilo di Storia Urbana, Alinea Editrice, Firenze 1995.

Annamaria Giusti, The Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence, Mandragora, Firenze 2000.

Francesco Gurrieri, et. al. La Basilica di San Miniato al Monte à Firenze, Ed. Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, Firenze 1988.

Walter Horn, “Romanesque Churches in Florence,” The Art Bulletin, XXV 1945.

Alta Macadam, Blue Guide – Florence, WW Norton, New York 1991.

G. L. Maffei, La Casa Fiorentina Nella Storia Della Cittá, Marsilio Editori, Venezia 1990.

Roberto Martucci and Bruno Giovannetti, Florence: Guide to the Principal Buildings, Canal and Stamperia Editrice, Venice 1997.

Alick McLean,“The Multiple Thresholds to the Cult of St. Minias at Florence’s San Miniato al Monte,” unpublished manuscript.

Franco Pratesi, La Splendida Basilica di San Miniato a Firenze – Il Rinascimento Inizia da Qui, Octavo, Firenze 1995.

Ferdinand Schevill, Medieval and Renaissance Florence – Volume I: Medieval Florence, Harper and Row, New York 1963.

Robert Tavernor, On Alberti and the Art of Building, Yale University Press, New Haven 1998.

Marvin Trachtenberg, Dominion of the Eye, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (UK) 1997.

italy magazine

Detail from the “Carta della Catena” of 1471, showing San Miniato al Monte.

“The so-called “Pianta della Catena” attributed to Francesco di Lorenzo Rosselli between 1471 and 1482, is the first known example in the history of cartography intended as a complete representation of the city of Florence, Italy, including all of its buildings and dense network of streets and squares. The name derives from the padlocked chain (Italian: catena) that frames the map. The artist, depicted from behind in the right foreground while sketching the walls of the city on a sheet of paper, draws attention to the author’s perspective from the southwest of Florence, illustrated as a “bird’s eye view” conforming to the medieval genre but with modern intentions of perspective realism.”

Firenze Musei

Sailko--Wikimedia Commons

Enjoy Firenze--uncredited

Treasures of Florence--uncredited

Top to bottom:

Detail of Baptistry San Giovanni

Detail of San Miniato al Monte

Detail of Foundling Hospital

San Miniato al Monte, left, and Santa Maria Novella, right, to the same scale.

Facade detail from San Miniato, top, compared to marble floor detail from Santa Maria Novella, right.

This aerial photo shows all too well the "clutter" that accumulated over the centuries, since 1207, filling in every corner of the fortress.