2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Development of Regent Street: An Amazing Event of Turns?

An Appreciation of John Nash and an Homage to Edmund Bacon

Project Scope

Creation of a major, new urban street to connect one Crown property with another— creation of Regent Street in London to connect Carlton House, home of the Prince Regent, to Regent’s Park.

Primary Protagonists

John Nash, architect

The Prince Regent (a king-in-waiting), later to become King George IV

Period of Intervention

Circa 1806—through the late 1820’s

1811—pivotal year; a long-term lease on lands of Marylebone was to revert to the Crown

1812—1828 construction of Regent’s Park

1813—1827 construction of Regent Street; the majority of building between 1818—1820

The Client

The client was the Prince Regent, later to become King George IV. His residence at the time was Carlton House, related to, but physically separate from, Buckingham House (now Buckingham Palace). Since the time of Henry VIII, the royal family, or “Crown,” owned farming and hunting lands to the north and just outside the city in an area called Marylebone. These lands had been leased to the Duke of Portland for agricultural use; but the lease was about to revert to the Crown, leaving the obvious question: what to do with this undeveloped land?

The First Proposals – John White

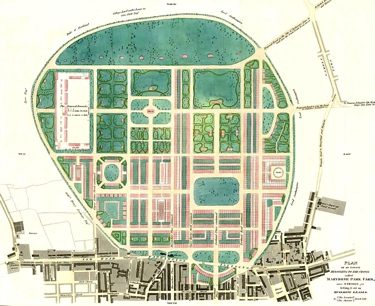

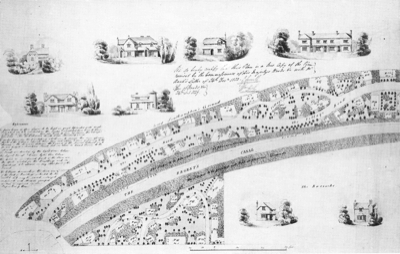

In anticipation, both the Prince Regent and the Duke of Portland had requested development proposals. The Office of Woods and Forests prepared plans for the Prince Regent as early as 1806. John White, a surveyor, prepared one for the Duke of Portland in 1809; neither was satisfactory to the Prince Regent. [Figure 2; see also Figure 12]

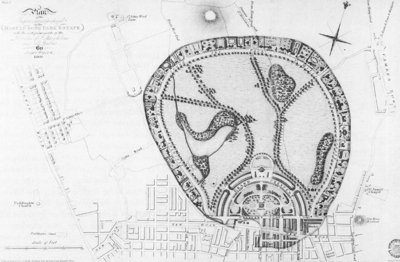

All the same, the plan by John White proposed retention of the land as a park, creation of a lake and peripheral residential development, some in the form of terraces. This represented a clear departure from contemporary residential development plans at nearby St. John’s Wood and promoted influences that were gaining acceptance in Great Britain. See below. [Figures 1 and 3; also, Figures 2, 6 and 7]

Nash Enters the Scene

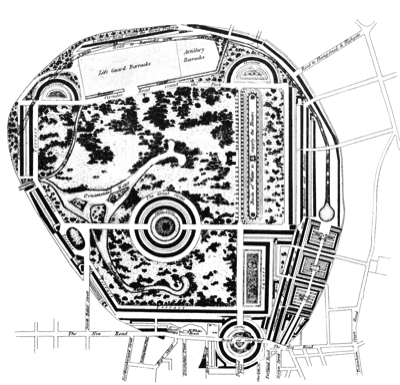

John Nash was an architect specializing in residential design and semi-rural development. [Figure 4] Up to this time, he had had a mixed career as a designer/developer, which had bankrupted him and drove him from London to live in Wales for twelve years. Through charm and the right contacts he became friends with the Prince Regent and, at age 58, he was requested to take the position of Architect to the Office of Woods and Forests. Thereby, Nash assumed responsibility for the development of the Crown lands and the street connector. His initial plans reflected his cottage-style background, but the influences from the John White plan began to appear and ultimately were developed to a higher level. [Figure 5]

What Were These Influences?

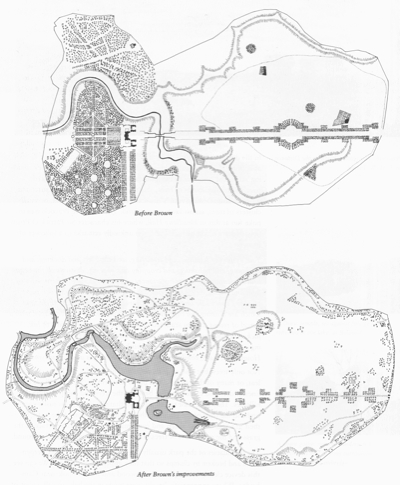

Lancelot “Capability” Brown was an influential landscape architect that gave the English designed garden its “look.” Comparison of the earlier plan of Blenheim shows formal gardens in the Italian/French manner. After redesign by Brown, he has introduced a bucolic look and emphasized the importance of the lake in the foreground. [Figure 6]

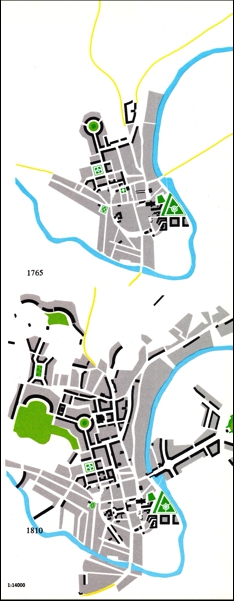

The development of Bath, below, can be characterized by the development of highly architectural residential terraces in juxtaposition to an informal, natural setting. The circus [a], in the middle of the orthogonal street pattern, developed into the open form of the Royal Crescent [b], and then into the undulating form of the Landsdowne Crescent [c]. [Figure 7]

Nash Design Intents

For Regent's Park, Nash’s first plan expanded the proposal by John White by including housing forms set into the center of the park, developing the perimeter for terrace housing and intending much of the park to be rural with canals, lakes and islands. [Figure 5]

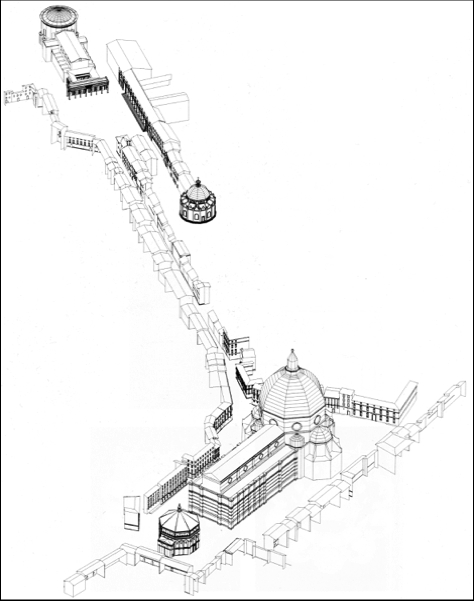

For Regent Street, the ideal concept would have been to make a straight connector from Carlton House to Marylebone—a Via Triumphalis; a Royal Mile—such as Via de’ Servi in Florence, improvements in Rome under Sixtus V, or a cours as had been developed in Paris. [Figures 8, 9, and 14] Immediately, reality set in; the axial alignment of Portland Place by Robert Adams did not correspond to this alignment; and, not all property owners were willing to sell their property, at least not cheaply. Therefore the first plan by Nash already introduced various “adjustments.” Then, as work proceeded, many more obstacles and opportunities were incorporated that gave the completed plan its distinctive character. [See page 5, for walkthrough from Carlton House into Regent's Park]

The black areas on the walkthrough map, below, indicate those buildings designed by Nash, or under his direct design control, to implement his grand plan. In some cases, as with the Great Quadrant, when no investors could be found, Nash put up his own capital to complete the project. His area of intervention extended not only to Regent’s Park to the north, St. James Park and Green Park to the south [a, b], but an addition to Buckingham Palace [c], and a proposed street connector to the British Museum [d].

Walkthrough—starting from the bottom

9 The point of the procession is the arrival in the park, where, in 1851, you could catch a hot air balloon ride to look back where you started.

8 When Nash heard about another new church to be built near York Terrace—Marylebone Church— he modified the design of York Terrace to permit a visual connection with the park.

6, 7 When one finally enters Regent’s Park the elegant residential terraces frame the view on the right (east) with Cumberland Terrace and on the left (west) with York Terrace.

5 North of Oxford Street a jog had to occur that could not be finessed. When Nash heard about a new church—All Souls Church—to be built near this location, he persuaded the developers to shift its orientation and alignment to the street to provide the sharp turn.

4 Having crossed Oxford Street we look backward to observe how skillfully another shift in alignment was achieved by the introduction of rounded facades, designed by Nash.

3 Continuing northward we round the expansive sweep of the Great Quadrant introduced to realign the street around unwilling property owners. Since it had to be constructed in one piece, Nash couldn’t find investors for this development and became his own investor/ developer to complete this piece of the puzzle. This time he did not go bankrupt.

2 Along the way northward a break in the street pattern produces a view to the right looking at the new facade of Haymarket Theatre, designed by Nash.

1 The view from Carlton House looking north towards the first juncture, the beginning of the Great Quadrant—the County Fire Office—an insurance company that Nash persuaded to occupy that location, and for whom he then designed its headquarters.

Conclusion – So What is the “Procession”?

What it was not created for:

* No military motives or crowd control…

* No royal procession after all…the Prince Regent became king during all this! Carlton

House was torn down and replaced with Carlton House Terrace, designed by John Nash

* Not a space intended for public demonstrations…

What it became:

* A promenade, a shopping street, a street on which to be seen

* Perhaps first truly public commercial shopping street

* A street based on land speculation to upgrade development of the West End; the manner in which the upper classes would be tempted to buy and build in the West End

Was there a hidden motive?:

* The Rome comparison, above, was an afterthought, added in 2020; but, it made me think that perhaps the underlying motive, as with Pope Julius II, was to allow the Prince Regent to go between his house and his park and also avoid the rabble.

Bibliography:

Edmund Bacon, Design of Cities, Viking Press, New York 1967.

Wolfgang Braunfels, translated by Kenneth Northcott, Urban Design in Western Europe: Regime and Architecture. 900 - 1900, University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1988.

Ylva French, Blue Guide London, WW Norton, New York 1991.

Mark Girouard, Cities and People: A Social and Architectural History, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1985.

Emil Kaufmann, Architecture in the Age of Reason, Harvard University Press 1955; reprint: Dover Publications, New York 1968.

Charles Moore, William Mitchell and William Turnbull, The Poetics of Gardens, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA and London 1988.

Alistair Service, The Architects of London and Their Buildings from 1066 to the Present Day, The Architectural Press, London 1979.

John Summerson, Georgian London, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA and London 1978.

Gabriele Tagliaventi, Alla Ricerca della Forma Urbana, Patron Editore, Bologna 1988.

Robert Tavernor, On Alberti and the Art of Building, Yale University Press, New Haven 1998.

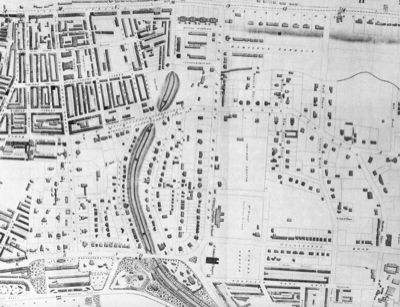

Figure 1: St. Johns Wood in 1807. Detail from the 1807 edition of Horwood's map of northwest London. [Girouard, p. 276]

Figure 2: Proposed development of Marylebone Park; John White 1809. (Westminster City Archives) [Girouard, p. 278]

Figure 3: “Lines of Beauty” in Capability Brown’s landscape plan for Bowood, Wiltshire [Moore, et. al. p. 60]

Figure 4: John Nash’s original plan for Park Village, Regent’s Park (Public Record Office) [Girouard, p. 280]

Figure 5: John Nash’s early plan for development of Regent’s Park of 1814 [Bacon, p. 188]

Figure 6: The garden at Blenheim Palace, before [1705 by John Vanbrugh] and after Capability Brown’s re-design [1760]. [Moore, et. al. p. 64]

Figure 7: Evolution of Bath, England between 1765 and 1810. [Bacon, p. 171]

Figure 8: Axonometric of Via de’ Servi connecting Piazza del Duomo with Piazza Annunziata in Florence. (Olivetti/Alberti Group) [Tavernor, p. 148]

Figure 9: The “cours” on the Boulevard St. Antoine. (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris) [Girouard, p. 176]

What Are Various Reasons for Modifying Street Patterns?

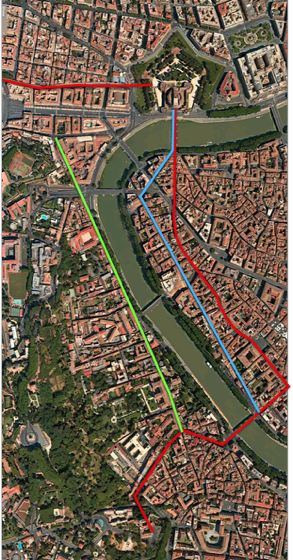

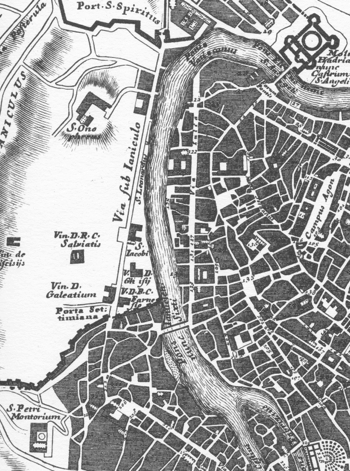

In addition to the processional street—Via de' Servi, and the promenade—the Cours, using Rome as an example, we can identify three more reasons:

1) Military protection

2) Wayfinding

3) Rabble, rubble and rubbish avoidance

a

b

c

d

c

a

b

Figure 13: You don't need to be a military engineer to guess the reason these three streets were straightened and realigned. The Popes were not always respected in the history of Medieval Rome. Castel Sant'Angelo was the White House bunker of the Vatican. Until the construction of Ponte Sisto, downstream, this was the only bridge across the Tiber near the Vatican. The alignment allowed cannon to be placed at the foot of the bridge. Most of Rome does not exhibit this as a motive, in contrast to the Haussmann interventions in post-Revolution of 1848, Paris.

Figure 14: Every six year old knows about the interventions by Pope Sixtus V, in preparation for the Jubilee of 1600. These new alignments were not for the purpose of city beautification, as much as wayfinding— connecting the religious and monumental dots—the pinball machine parti. Therefore, the alignments lack an inherent geometric order—the pickup sticks parti.

Figure 15: The red line shows the progression the Popes had to make through the rubble and rabble of Medieval Rome, let's say to reach San Pietro in Montorio, only to be pelted by garbage, at every turn. Via Giulia [named after Pope Julius II]—blue line—was designed to avoid the rabble and reach the Ponte Sisto and San Pietro. Later, Via Longara—green line—offered an even more direct route from the Vatican.

Military protection

Wayfinding

Rabble dodging

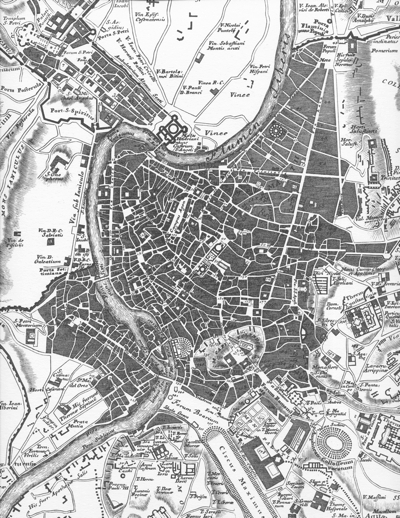

Figure 16: Some people just don't feel whole until they have studied a historic map. For those of you [you know who you are], at the top is a segment of the iconic Pianta di Roma of 1748, by Giambattista Nolli, which encompasses the three areas presented in Figures 13—15. You can use it to practice your map reading skills.

The lower map is Nolli's engraving based on a woodcut map from Leonardo Bufalini of 1551, which is more indicative of the Medieval character of Rome in the 16th Century.

Go ahead. Click. You know you want to. Nobody's Looking.

Click map segments, below, to see them really big

Apple Maps

Apple Maps

Apple Maps

Figure 18: Poor All Souls Church, top, seems isolated and overwhelmed by the scaleless Val Myer BBC Broadcasting House. Most of Regent Street has lost its intended charm, in part by the replacement by early 20th century buildings, but mostly from incessant traffic. The terraces along Regent's Park seem to have been better-respected, as was St Marylebone Church, bottom.

200 years later?

Click numbers on map to open images as popups. Click engravings to see them as full-size images.

Figure 10: These details from the remarkable maps by Richard Horwood of 1799, top, updated by William Faden in 1819, bottom, best demonstrate the John Nash interventions during the 20-year period. The red dashed line shows the alignment of Portland Place, created by the Adams Brothers during the 1770s; the blue line shows the alignment from Carlton House—the first problem for Nash, how to reconcile the two alignments.

RomanticLondon.org

RomanticLondon.org

Click maps to see them as larger images.

Figure 11: In this earlier attempt by Nash to reconcile the two alignments he thought he had it made by introducing the broad sweep of the Great Quadrant and then a bit of serpentine wiggling. But, other obstacles lay ahead—literally.

Visit RomanticLondon.org to see both maps in their entirety

Figure 12: A plan, of 1812, by Thomas Leverton and Thomas Chawner, of H. M. Land Revenues, nearly was selected over the Nash plan, since it would have been substantially more lucrative for the Crown, by proposing residential development—we would have no Regent's Park today.

Click plan to see as larger image.

ianVisits

Figure 17: This comparison of Rome in 1551 and London in 1799, to a similar scale, underscores the similarities between Pope Julius II and the Prince Regent in confronting a jumbled—undignified—urban fabric. Imagine Julius trying to cut through the city before Via Giulia. For the Prince Regent to get from Carlton House to Regent's Park offered no clear route until crossing Oxford Street and then reaching the visual safety of Portland Place.